breakthroughonskis.com

more than two decades of ski writing, ski teaching, and ski publishing by Lito Tejada-Flores

Ski Writing

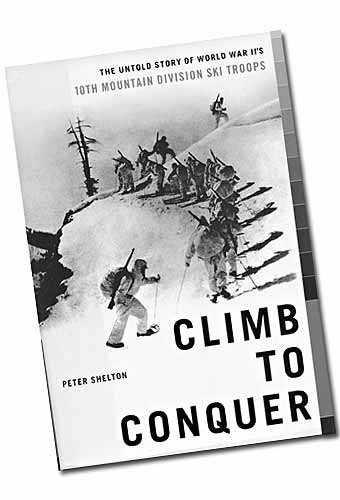

Climb to Conquer

the untold story of

the 10th Mountain Divison ski troops

a new book by Peter Shelton

Peter Shelton has been one of my favorite ski writers for longer than I can remember. I can't tell you what a pleasure it was to read his new book on the story, the people, the myth but above all the larger-than-life reality of the celebrated 10th Mountain Division, America's first and only real skiing soldiers. Peter's book has just been published and is now avalilable [if your local bookstore doesn't yet have it, they can order it from the publishers, Scribners; or you can order it

online from amazon.com].

Of course, this page, and my comments above, were posted

on my site, quite a few years ago, in January 2004.

So this is no longer a "new book," but it is still as good as

ever, a thrilling read.…

Here is the prologue to this terrific book.

Prologue

John Jennings, a 21-year-old infantryman with the 87th Regiment of the 10th Mountain Division, steadied his ski and slipped one leather boot between the toe irons. In the darkness, he felt for the cable loop and positioned it around his heel. Then he snapped the forward throw closed — a familiar, comforting sound — locking his boot to the ski. Kneeling, he repeated the process with the other boot and binding. It was January 1945. Snow coated the cobblestone streets of Vidiciatico, a medieval farming village in Italy’s North Apennines Mountains. A few miles to the north, the German army had dug in for the winter along a series of high ridges, forming a defensive shield that U.S. Army mapmakers dubbed The Winter Line.

The hills here reminded Jennings of the hills around Hanover, New Hampshire, where he had completed three semesters at Dartmouth College before reporting to the Army in February 1943. Monte Belvedere, the mountain directly in front of Vidiciatico, sloped up gradually to a long, whaleback ridge at 3,800 feet. Sharp ravines etched the mountain face in a few places, but most of the ground was cultivated in a patchwork of tilted fields and hedgerows, woods and orchards nearly to the top. Now, of course, the fields lay dormant under a thin, mid-winter snowpack. Lit by a partial moon, individual crystals sparkled between the shadows. It was the kind of night that Jennings would have considered beautiful back home in Massachusetts. It was beautiful, in spite of the deadly game he was playing.

Jennings’ 10-man patrol would have to maneuver, at least part of the night, in the open, and so they wore their camouflage “whites,” knee-length poplin anoraks, over their olive-drab uniforms. Their skis were painted white, too, as were the bamboo shafts of their ski poles and the camo-white pack covers. A lot of their gear, though, developed specifically for the Mountain Division during its training in Colorado, had not made the crossing to Italy. Or if it had, not much of it had been delivered to the front lines. The soldiers missed their lug-soled mountain boots and their custom mountain rucksacks. They didn’t have their white pants or their white canvas gaiters to keep snow out of their boots. Their high-peaked four-man mountain tents were nowhere to be seen, and instead of cozy, double down sleeping bags the soldiers huddled under thin Army blankets. Fortunately, most of them were billeted indoors, out of sight of German observation, in nearby barns and farmhouses. The supply sergeant who brought the skis and anoraks up from Florence couldn’t find any climbing wax, so Jennings and the patrol had “borrowed” candles from Italian families and rubbed candle wax into their ski bases instead. At midnight, they slipped out of Vidiciatico toward Belvedere. It felt good, Jennings thought to himself, to have the boards on his feet again.

At Dartmouth he’d been a four-event man—jumping, cross-country, downhill and slalom. But his first choice following Pearl Harbor had not been the Army’s newly formed ski troops. He had wanted to join the Navy. His mother’s family came from the Vermont side of Lake Champlain, near where the Battle of Plattsburgh was fought during the War of 1812. Relatives told stories about the British invaders sailing down the lake from Canada raiding farms along the way only to be defeated in the decisive naval battle off Plattsburgh. The smaller American fleet won with stunning certainty, thus preventing the invasion of New York via the Hudson River Valley. Sailing held the real romance for Jennings. But the Navy wouldn’t take him because he wore glasses. As his second choice, he volunteered for the 10th Mountain Division. “At least,” his father reasoned, wrongly, as it happened, “you won’t be sent overseas.”

The patrol skied in silence, single-file through moonlit stands of leafless oak and chestnut trees. Warm days and freezing nights had left an icy crust on the snow surface. It supported the skiers’ weight most of the time. Now and then, the crust collapsed, and their skis broke through, knee-deep, into the sugary hollow below. Without skis, it would not have been possible to go even a hundred yards; a man on foot would simply flounder. Jennings labored under the extra weight of a Browning Automatic Rifle, a heavy though effective relic of World War I. Its firepower lay somewhere between that of a machine gun, which would have been too cumbersome for one man to ski with, and the standard-issue M-1 rifle. It took a twenty-round clip and could fire singly or in automatic bursts. Still, the BAR weighed twenty pounds, more than double the heft of the M-1, and Jennings also lugged twenty pounds of .30-caliber ammunition on his belt.

Because of the weight, Jennings broke through more than the riflemen did. It took more energy to free his ski tips and climb back to the surface, but he was a strong kid and a good skier. He’d grown early, to six feet and 175 pounds while still in high school at Cushing Academy. His 1939 football team went undefeated and untied as New England prep school champs, and as a member of Cushing’s travelling ski team, he had competed on the boards for years. At Camp Hale, Jennings’s skills led him into the elite Mountain Training Group, or MTG, with the men who designed and taught the courses in skiing and mountaineering, the ones who led the training missions onto the rocks and snow. Jennings thought back now to those halcyon days in Colorado. The war hadn’t seemed quite real then, and it still didn’t — not at the deepest gut level. The 10th had been on the line only a few days. Except for the patrols, there hadn’t been much to do but stay hidden and keep warm. Jennings had not squeezed off even one shot with the BAR.

For three hours the squad zigzagged uphill toward its objective on Belvedere’s west flank. The goal was an abandoned farm near the ridgeline. Were there Germans there? If so, how many? Did it look as if they’d occupied the place for a while? Were they dug in to defend or just passing through? The goal was not to fight any German soldiers they might find there, or win territory. Neither side was attempting, at this point in the winter, to gain ground. The cold and snow, the inability to move vehicles and artillery, had locked both sides into an uneasy stalemate. Still, both sides sent patrols across the line nearly every night, to probe, to learn what they could, and if they happened to get lucky, to bring back a prisoner for interrogation.

Most patrols never fired a shot. Medic Bud Lovett joined a pre-dawn ski patrol west of Belvedere outside the town of Bagni di Lucca. The squad skied quietly uphill, until some time after sunrise they spotted a lone German in camouflage whites standing on a connecting ridge. The patrol’s orders included bringing back prisoners if possible, so the squad leader called out for the trooper to halt, put his hands on his head and “come in.” A beat elapsed. Then another. Then the German jumped his skis 90 degrees into the fall line and schussed straight down the steep slope in front of him, “like going down Tuckerman’s,” Lovett thought. “He was some skier.” So impressed were the Americans that no one even thought to take a shot at him as he fled.

When Jennings’ squad found the farmhouse, the officer in charge spread the men out in the field below it. Jennings was to set up his B.A.R. on a haystack and provide cover while two scouts moved forward toward the buildings. Jennings wondered why. From where he crouched he could hear Germans talking and digging in the rocky ground, digging a machine-gun placement perhaps. The Americans should get out now before it got too light. They were right under the enemy’s nose, and in full daylight they would surely be spotted.

The eastern sky brightened. Shadows sharpened as the snow took on a dawn glow. Seconds felt like minutes. And minutes stretched too far in both directions, into memory and fear. “Why was it taking so long?” Jennings thought. “We’re not going to able to take a prisoner in broad daylight. We’re way out in the open here. No trees for hundreds of feet below the meadow. No cover. If the enemy has even one machine gun . . . Why don’t they hurry up?” Jennings, a private first class, was not in charge. All he could do was shift his feet — skis attached—to a slightly more comfortable position under him, and wait. He hadn’t exactly volunteered for these patrols. The S2 (intelligence officer) for 2nd Battalion had spotted him in Vidiciatico, knew him to be a Dartmouth skier and MTG guy, and “volunteered” him for these night patrols. He hadn’t minded the duty until now. The skiing with heavy packs, that was okay — they’d trained for that — but this agonizing waiting . . .

When the scouts finally scrambled back, the sun was nearly up. Jennings flung the BAR on his back and pushed off down the hill, skating and poling as fast as he could. All ten squad members raced through the growing light for the trees at the base of the meadow certain that the enemy at their backs had spotted them. Jennings fought for balance on the collapsing crust. Climbing slowly uphill through tricky snow was one thing; this high-speed flight was quite another. The weight of the BAR threatened constantly to pitch him on his face. Now they were in the first small trees, just sticks really, dodging left and right around them. “This has got to be the hardest slalom I’ve ever raced,” Jennings thought. And then he saw the machine gun fire kicking up puffs of snow on either side of him. They had been discovered.

The bullets swept the snow in a predictable geometry a few feet behind the fleeing Americans. If any one of the patrol were to fall, he would surely be raked where he lay. Out of the corners of his eyes, Jennings checked the others flying as he was over the snow, all still upright, skiing for their lives.

Legs pumping, skis singing with the speed, Jennings and his BAR dodged the last scrub oak into the clear, out of sight from above. They’d made it. They were free now to coast back down their ascent track, almost as if they were out for a casual ski tour in the Berkshires, say, or the Adirondacks, back to the safety of the line — and what awaited them next.

Click HERE to send Lito an email